ForbiddenParadise64

Scribe

Scribe

The Clockwise World

New canon map V6 by Molotovsnowman as of March 1, 2024.

Biome map by Molotov too

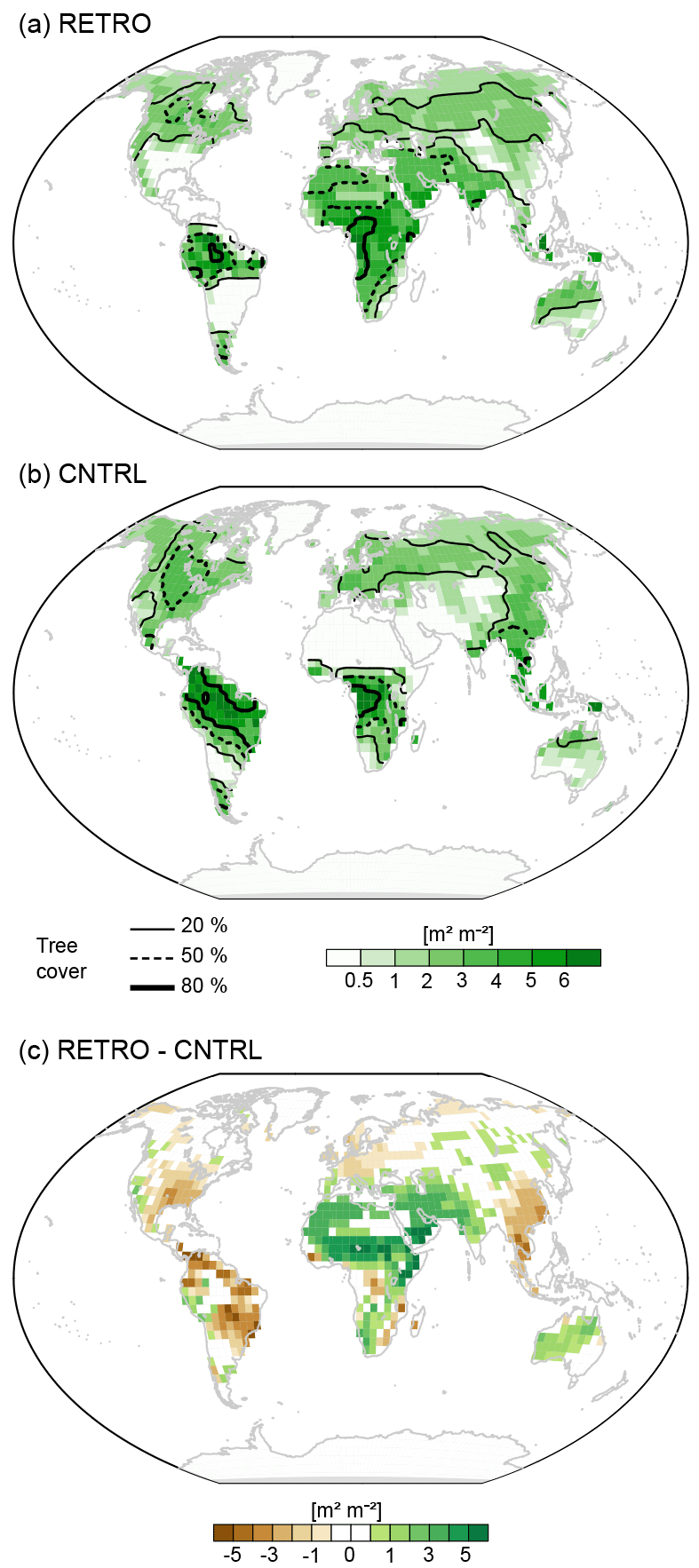

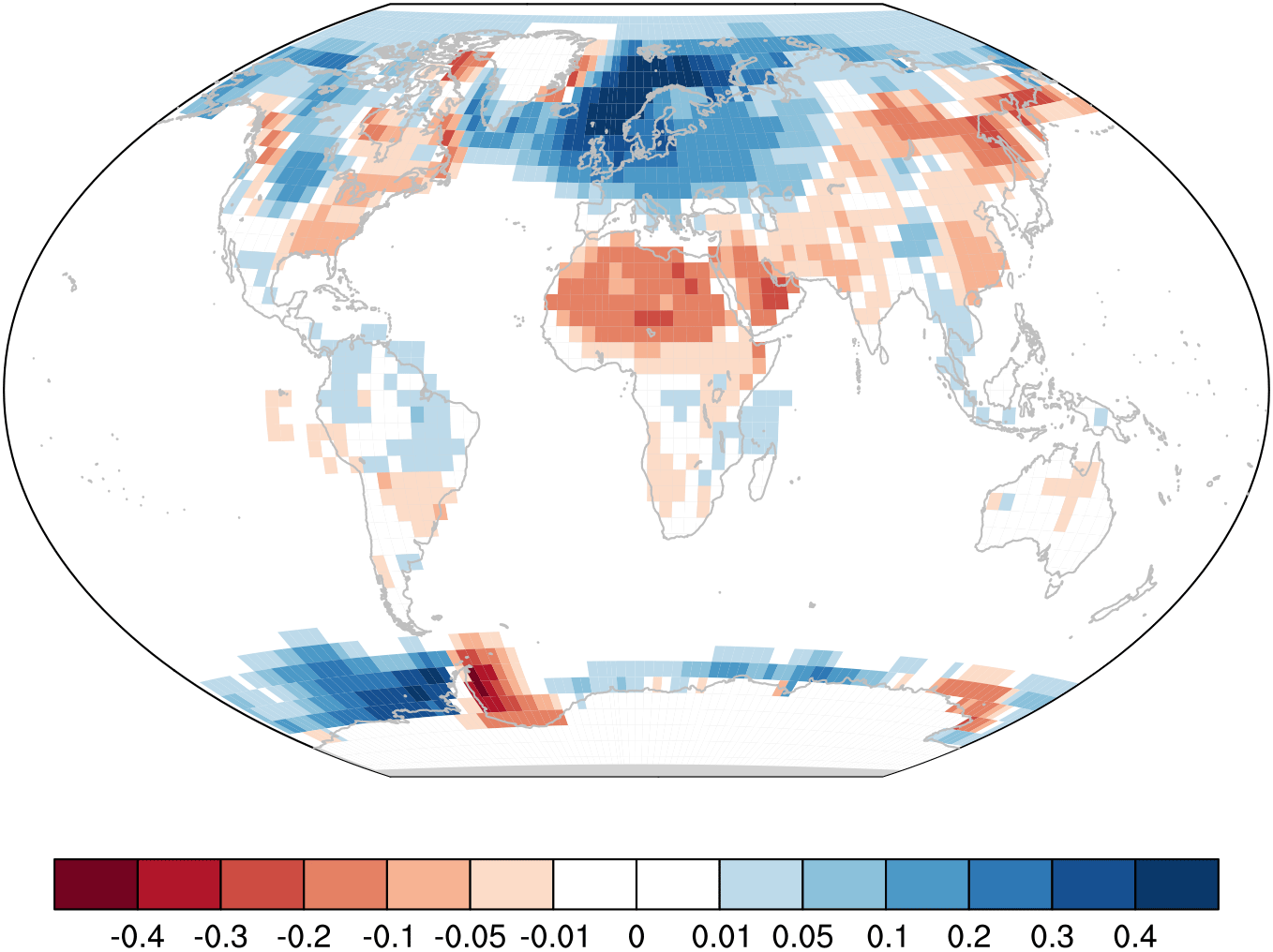

Keep in mind this map assumes preindustrial CO2 levels. According to a quick Google search, otl earth has warmed up by roughly 1.1C since the start of the Industrial Revolution thanks to anthropogenic climate change, and according to the study data, retrograde earth is about 0.14C cooler globally than prograde, though the division between hemispheres isn’t even, with the northern hemisphere being 0.55C cooler on average and the southern hemisphere being 0.28C warmer on average compared to preindustrial prograde. So keep this all in mind when comparing places to their otl locations.

There are many circumstances and unexplained phenomena that can be offered a plausible and physically possible situation. What happened 1.5 million years before the present day in this alternate timeline was not among them.

The world of the early Pleistocene was a time of interesting changes. In the early part of the infamous ice ages, the world was about to slip from a brief interglacial into a frigid glacial period, along with all the faunal upheavals that would cause. It was also a major part of human evolution, as Homo erectus was widespread across Africa and was beginning to make fire. Some humanoids had even migrated into southern Asia, with some erectus populations reaching as Far East as Java. This complicated time was about to get even more so.

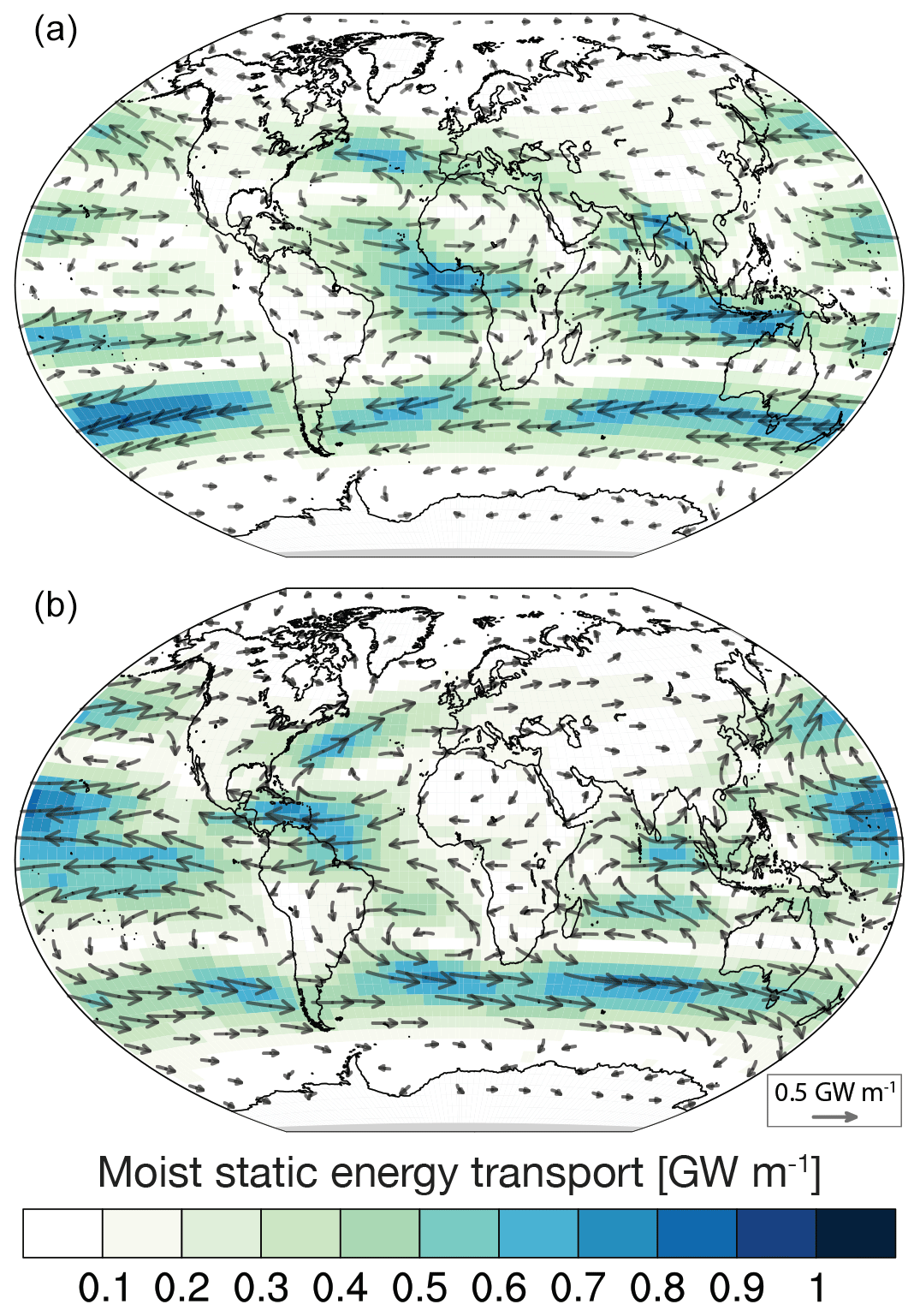

The reversal of Earth's spin was not instantaneous, as such an event would cause untold devastation, but occurred over a period of just a year. After eighteen months, it seemed as if the day would stop spinning altogether. Animals and early humans experienced great shock and terror in these early times, and there was confusion among migration patterns and sleep patterns. But after six months, the earth started spinning again. But this time, the sun rose in the west and fell in the east. At first, this seemed an insignificant change in the long term, but one doesn't have to be a geological expert to review the great changes the world would go through. Within millennia, climates around the world were rendered nearly unrecognisable in some places.

With the Earth's motion going differently, the winds and ocean currents also began to alter their shapes, and reverse in many cases. Already in the midst of the Pleistocene ice ages, turmoil around the world created an even more unstable environment. The Coriolis effect went into reverse as well. Some places began to become hotter and drier, with forests being replaced by grasslands and then deserts, while in others the reverse happened. The former occurred mainly on the western shores of oceans, such as the east coast of America and east Asia, while the latter occurred on the eastern shores. In some places, due to more complicated procedures, neither extreme happened, with a few places being colder and drier or warmer and wetter. Those places furthest from the sea such as Central Asia and central Africa were the least affected, but in time they too saw other changes from the surrounding lands.

New canon map V6 by Molotovsnowman as of March 1, 2024.

Biome map by Molotov too

Keep in mind this map assumes preindustrial CO2 levels. According to a quick Google search, otl earth has warmed up by roughly 1.1C since the start of the Industrial Revolution thanks to anthropogenic climate change, and according to the study data, retrograde earth is about 0.14C cooler globally than prograde, though the division between hemispheres isn’t even, with the northern hemisphere being 0.55C cooler on average and the southern hemisphere being 0.28C warmer on average compared to preindustrial prograde. So keep this all in mind when comparing places to their otl locations.

There are many circumstances and unexplained phenomena that can be offered a plausible and physically possible situation. What happened 1.5 million years before the present day in this alternate timeline was not among them.

The world of the early Pleistocene was a time of interesting changes. In the early part of the infamous ice ages, the world was about to slip from a brief interglacial into a frigid glacial period, along with all the faunal upheavals that would cause. It was also a major part of human evolution, as Homo erectus was widespread across Africa and was beginning to make fire. Some humanoids had even migrated into southern Asia, with some erectus populations reaching as Far East as Java. This complicated time was about to get even more so.

The reversal of Earth's spin was not instantaneous, as such an event would cause untold devastation, but occurred over a period of just a year. After eighteen months, it seemed as if the day would stop spinning altogether. Animals and early humans experienced great shock and terror in these early times, and there was confusion among migration patterns and sleep patterns. But after six months, the earth started spinning again. But this time, the sun rose in the west and fell in the east. At first, this seemed an insignificant change in the long term, but one doesn't have to be a geological expert to review the great changes the world would go through. Within millennia, climates around the world were rendered nearly unrecognisable in some places.

With the Earth's motion going differently, the winds and ocean currents also began to alter their shapes, and reverse in many cases. Already in the midst of the Pleistocene ice ages, turmoil around the world created an even more unstable environment. The Coriolis effect went into reverse as well. Some places began to become hotter and drier, with forests being replaced by grasslands and then deserts, while in others the reverse happened. The former occurred mainly on the western shores of oceans, such as the east coast of America and east Asia, while the latter occurred on the eastern shores. In some places, due to more complicated procedures, neither extreme happened, with a few places being colder and drier or warmer and wetter. Those places furthest from the sea such as Central Asia and central Africa were the least affected, but in time they too saw other changes from the surrounding lands.

Myth Weaver

Myth Weaver Auror

Auror